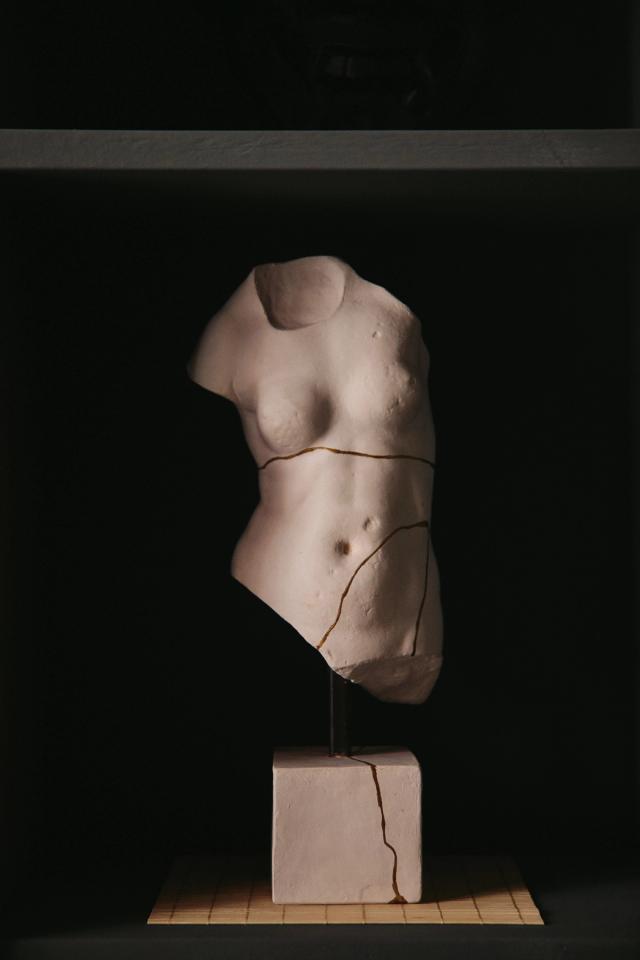

Kintsugi is the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. Instead of hiding the cracks, kintsugi highlights them, finding beauty in imperfection. Its name derives from “Kin” gold – “tsugi” reunion.

We were introduced to Anita Cerrato by our friend Romi Loch Davis, who describes her first encounter.

Anita Cerrato is wonderfully unassuming, dedicated, and devoted—a true "Maestra." I first met her during a delicate time in my life, and she instinctively sensed how and where to tread without reopening old wounds.

After my mother's death, my dear friend Hisako Shibata gifted me a kintsugi ceramic. Unfortunately, it broke again. Anita repaired it and then gifted it back to me in a profoundly healing and unforgettable gesture.

"For me, Anita represents "double kintsugi"—layers of restoration. She ennobles, shares, soothes, and mends what has already been repaired, even when it cracks again. Anita is a balm for the heart and a source of healing for the spirit.

- Romi Loch Davis

“With kintsugi, I have made a ‘kintsugi’ of my life,” Anita Cerrato, says.

After an extensive career in furniture restoration, Cerrato sought to “reinvent” herself through her profession. The fact that she made kintsugi (giving ceramics and similar objects a brilliant second life through the beauty of their repairs) the center of this professional rebirth is almost too poetic not to emphasize—and indeed, Cerrato sees the parallels, too.

Armed with a supply of fine gold leaf bestowed by a retiring craftsman, Cerrato originally set out to craft wooden objects covered in gold. However, a quick scan of images on the internet fortuitously introduced her to the art of Kintsugi. She immediately fell in love with it in all its forms: the philosophy, the technique and craftwork, and, of course, the finished product. So Cerrato did what any true artisan resolute in perfecting her skill set would do: she went to Japan to study the craft at its source. There, she trained under esteemed master Takaiko Sato and then Matsuda Shokan Sensei, a notable master in maki-e lacquer techniques with whom she continues to study (“I try to visit him every year or so.”)

Now, in her serene and spacious atelier in southern Milan, Cerrato has created a space where brokenness is not an end but a beginning—a setting where passion and patience intertwine, allowing the shattered to become whole again.

In a way that truly makes the craft her own, Cerrato also developed an exceptional method for applying kintsugi to old photographs. The technique took three years of research to find the right compromise between a lacquer requiring high levels of humidity and photograph paper that tends to damage easily under such conditions. But the effort paid off, as seen in the exquisitely haunting photographs on Cerrato’s studio website.

Kintsugi and urushi tsugi on photography. See more here

"I was born in Milan but chose to live in the countryside for many years. However, work brought me back, as Milan is the hub of business in Italy. Luckily, I found a space with a small courtyard, which allows me to pursue my passion for botany in a small way."

"The restoration process occurs in three phases: gluing, filling, and gilding. Each project can easily take up to 3 months."

Most recently, Cerrato embarked on a lengthy restoration project consisting of a collection of Chinese vases damaged in a wartime bombing. She received seventeen crates containing more than 250 fragments. The extensive process represents both a professional undertaking and a personal journey—but, much like kintsugi itself, the beauty lies in the experience as much as in the final product.